Building AI-Friendly Scientific Software: A Model Context Protocol Journey

In this post, I walk through building a remote Model Context Protocol (MCP) server that enhances AI agents’ ability to navigate and contribute meaningfully to the complex Napistu scientific codebase.

This tool empowers new users, advanced contributors, and AI agents alike to quickly access relevant project knowledge.

Before MCP, I fed Claude a mix of README files, wikis, and raw code hoping for useful answers. Tools like Cursor struggled with the tangled structure, sparking the idea for the Napistu MCP server.

I’ll cover:

- Why I built the Napistu MCP server and the problems it solves

- How I deployed it using GitHub Actions and Google Cloud Run

- Case studies showing how AI agents perform with — and without — MCP context

The AI development paradox

We’re at an interesting inflection point in software development. AI both accelerates and hinders the creation of high-quality code.

✅ Acceleration

AI speeds up development by:

- Handling repetitive tasks

- Lowering the barrier to entry

- Simplifying debugging

Sometimes I hand an agent a stack of failing pytest errors and say,

“You handle this.” And it does. It’s pure magic.

❌ Friction

But AI also introduces chaos:

- Repeats patterns instead of reusing code

- Misses domain-specific idioms

- Adds unnecessary abstractions

- Produces brittle, poorly-structured code

This goes beyond simple messiness — it can rapidly escalate into a technical debt time bomb.

🎯 Key Insight

AI isn’t inherently good or bad; its performance is task-dependent. Most AI failures can be traced back to missing context: the model simply wasn’t given the information it needed to succeed. If an AI agent understands your domain, your design patterns, and your project structure, it can generate excellent code. Without that context, it’s flying blind — and that’s where most of the frustration comes from.

Many of us are seeking the optimal balance where AI maximizes productivity, while simultaneously working to expand that potential by enhancing its performance on critical tasks.

Information is everything

Context is the central challenge in any domain-specific codebase — be it a financial trading system, a game engine, or a scientific library. Until AI agents understand the context of the codebase, they will struggle to follow existing patterns and conventions, and misuse domain-specific approaches.

Off-the-shelf approaches to AI integration are improving, either by seamlessly integrating with external services (like Claude talking with GitHub, Google Docs, etc.), or by directly interfacing with the codebase itself (as tools like Cursor and Copilot do). But, as you’ll see, while these options help, they still leave something to be desired.

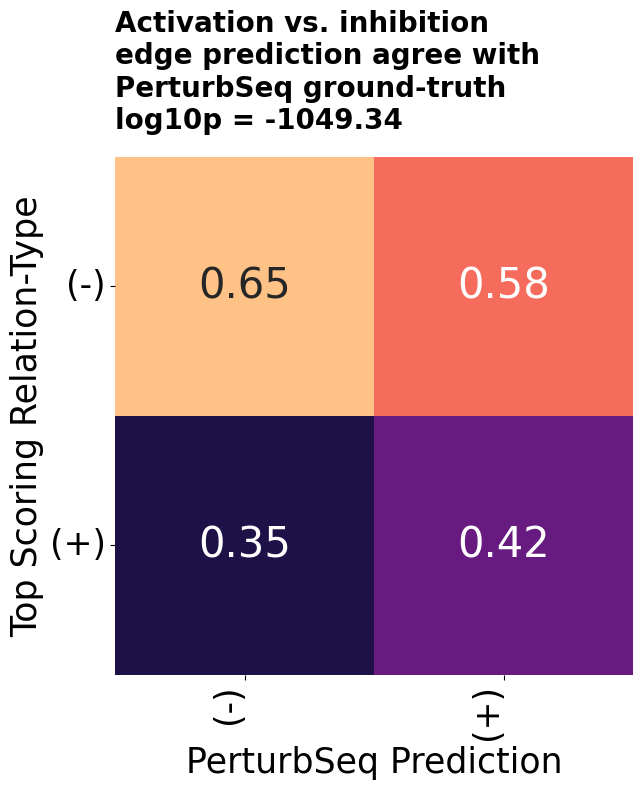

Case study: the value of context

To highlight the value of context, I’ll use a real-world example. Say I ask an agent to help me with the following question:

How do I create a consensus network from multiple pathway databases in Napistu? Please create a single artifact with your initial thoughts.

Let’s explore a few scenarios to see how this plays out.

Scenario 1: no context

Without any context, Claude has no idea what I’m talking about and starts Googling:

I’m not familiar with Napistu as a specific software tool or platform for pathway database analysis. … Since I cannot locate specific documentation for Napistu, I’ll create an artifact with general guidance on creating consensus networks from multiple pathway databases

Claude suggests some helpful ideas — but says nothing about Napistu.

Scenario 2: some context

With relevant code context, by pointing Claude to relevant .py files

from GitHub:

Looking at the Napistu codebase, I can see this is a systems biology toolkit for working with pathway models. Let me create a comprehensive guide on how to create a consensus network from multiple pathway databases.

The resulting

artifact

highlights key classes and functions, organizing them into a clear,

orderly progression. Nonetheless, the response feels disjointed, as if

it pulled snippets from many sources without adequately synthesizing

them. Moreover, producing this response required me to provide specific

.py files to Claude because only ~15% of the napistu.py codebase

could fit into Claude’s context window.

Scenario 3: expert knowledge

If you asked an expert (me, 🙃) this question, the guidance would draw from multiple information sources:

Start with the merging_models_into_a_consensus tutorial — it provides a step-by-step walkthrough of this exact workflow. Building consensus involves calling

consensus.construct_consensus_model()with multipleSBML_dfsobjects and a pathway index, which organizes the objects’ metadata. This is currently being reworked in Issue 169 to remove the pathway index requirement. Finally, review the consensus Napistu wiki page to gain a high-level understanding of the key algorithms.

This response demonstrates true understanding — it connects theory (the algorithm), practice (the tutorial), current development (the GitHub issue), and conceptual framework (the wiki) into actionable guidance.

Providing AI agents with expert knowledge

For an AI agent to match the expert response, we would need to do more than just expand its context window; we need to address two key challenges:

- information fragmentation - Relevant information is scattered across multiple sources such as code repositories, wikis, issue trackers, tutorials, README files, and more. This dispersion makes providing relevant information to agents a cumbersome and often manual process.

- signal vs. noise - Critical context can easily be obscured by large volumes of irrelevant or low-priority information, making it challenging for AI agents to identify what truly matters.

Solution preview: What if an AI could retrieve domain-specific information on demand?

Before diving into how to provide agent-friendly information, let me first show you the results of that effort in Napistu.

First, I’ll install Napistu with MCP dependencies enabled.

pip install 'napistu[mcp]'

Then, I can configure the remote documentation server’s URL and port

with production_client_config.

from IPython.display import HTML, display

from napistu.mcp.config import production_client_config

config = production_client_config()

display(HTML(f"""

<div>

<b>Client config:</b><br>

<b>Host:</b> {config.host}<br>

<b>Port:</b> {config.port}<br><br>

</div>

"""))

Host: napistu-mcp-server-844820030839.us-west1.run.app

Port: 443

Since this is a remote server, I can now start interacting with it directly. I’ll pose the consensus modeling question again and then reformat the AI-friendly JSON output as human-readable tables.

import html

import re

import pandas as pd

from napistu.mcp.client import search_component

from shackett_utils.utils import pd_utils

from shackett_utils.blog.html_utils import display_tabulator

def sanitize_content(text):

if pd.isna(text):

return ""

# Remove/replace problematic characters

text = str(text)

text = re.sub(r'[^\w\s\-.,!?():]', ' ', text) # Keep only basic chars

text = re.sub(r'\s+', ' ', text) # Normalize whitespace

return html.escape(text) # HTML escape

QUERY = "How do I create a consensus network from multiple pathway databases in Napistu?"

COMPONENTS = ["codebase", "documentation", "tutorials"]

# Returns actual Napistu function signatures, docs, and usage examples

combined_results = list()

for component in COMPONENTS:

results = await search_component(

component,

QUERY,

config=config

)

results_df = pd.DataFrame(results["results"]).assign(component=component)

combined_results.append(results_df)

combined_results_df = pd.concat(combined_results).sort_values(by="similarity_score", ascending=False)[["component", "similarity_score", "source", "content"]]

display_combined_results_df = combined_results_df.copy()

pd_utils.format_numeric_columns(display_combined_results_df, inplace = True)

pd_utils.format_character_columns(display_combined_results_df, inplace = True)

display_combined_results_df['content'] = display_combined_results_df['content'].apply(sanitize_content)

display_combined_results_df['source'] = display_combined_results_df['source'].apply(sanitize_content)

display_tabulator(

display_combined_results_df,

caption="Top search results by cosine similarity",

wrap_columns=["source", "content"],

column_widths={"source" : "25%", "content" : "50%"},

include_index = False

)

Because the top result is Markdown, I’ll display it as a blockquote.

import re

from IPython.display import Markdown

def quote_markdown(markdown_content):

suppressed_headings = re.sub(r"^#+ (.*)$", r"**\1**", markdown_content, flags=re.MULTILINE)

blockquoted = "\n".join(f"> {line}" for line in suppressed_headings.split("\n"))

return blockquoted

# Add blockquote formatting

markdown_content = combined_results_df["content"].iloc[0]

display(Markdown(quote_markdown(markdown_content)))

Tutorials

These tutorials are intended as stand-alone demonstrations of Napistu’s core functionality. Most examples will focus on small pathways so that results can easily be reproduced by users.

- Downloading pathway data

- Understanding the

sbml_dfsformat- Merging networks with the

consensusmodule- Using the CPR Command Line Interface (CLI)

- Formatting

sbml_dfsasnapistu_graphnetworks- Suggesting mechanisms with network approaches

- Adding molecule- and reaction-level information to graphs

- R-based network visualization

Much of the information that the expert provided is returned in this

initial query. However, the goal is not to deliver all relevant

information at once because this would inevitably include a significant

amount of irrelevant data. Rather, we can use tools like

search_component to give agents agency, putting information at the

tips of their virtual fingers. This allows agents to nimbly explore a

problem drawing upon relevant resources on-demand. As a result, rather

than generating generic or hallucinated responses, agents can uncover

actual patterns, locate pertinent tutorials, and gain a deeper

understanding of our domain-specific approaches.

Enter the Model Context Protocol (MCP)

MCP provides a standardized way for AI models to access external information sources. Think of MCP as giving AI agents a research assistant who knows your project inside and out — someone who can instantly locate relevant documentation, code examples, and domain-specific implementation patterns specific to your domain.

AI agents can interact with MCP servers through two primary mechanisms: tools and resources. Think of resources as reference materials agents can read (like a library catalog), and tools as actions they can execute (like asking a librarian to retrieve specific materials).

Let’s look at how this works in practice with the Napistu MCP server:

Tools enable agents to perform actions and searches:

search_documentation()- Find relevant project docs and issuessearch_codebase()- Discover functions, classes, and methodssearch_tutorials()- Locate implementation examples

The search_component function used in the solution preview above

indirectly uses a tool by calling the lower-level function

call_server_tools. call_server_tools in turn calls the actual

FastMCP Client method call_tool. This method accepts a tool name and

arguments, returning structured results.

Resources in Napistu MCP provide read-only access to structured information:

napistu://health- Server status and component healthnapistu://documentation/summary- Overview of available documentationnapistu://tutorials/index- Available tutorial content

To call a resource endpoint like napistu://documentation/summary in

Python, we can use the read_server_resource function, which calls the

FastMCP Client method read_resource. This method takes a resource

URI and returns the contents of the resource.

from napistu.mcp.client import read_server_resource

content = await read_server_resource("napistu://documentation/summary", config)

print(content)

{

"readme_files": [

"napistu",

"napistu-py",

"napistu-r",

"napistu/tutorials"

],

"issues": [

"napistu",

"napistu-py",

"napistu-r"

],

"prs": [

"napistu",

"napistu-py",

"napistu-r"

],

"wiki_pages": [

"Environment-Setup",

"Data-Sources",

"Napistu-Graphs",

"Model-Context-Protocol-(MCP)-server",

"SBML-DFs",

"SBML",

"Dev-Zone",

"Exploring-Molecular-Relationships-as-Networks",

"Precomputed-distances",

"GitHub-Actions-napistu‐py",

"Consensus",

"History"

],

"packagedown_sections": []

}

This architecture solves our earlier problem; instead of manually curating context, AI agents can dynamically discover and retrieve exactly the information they need.

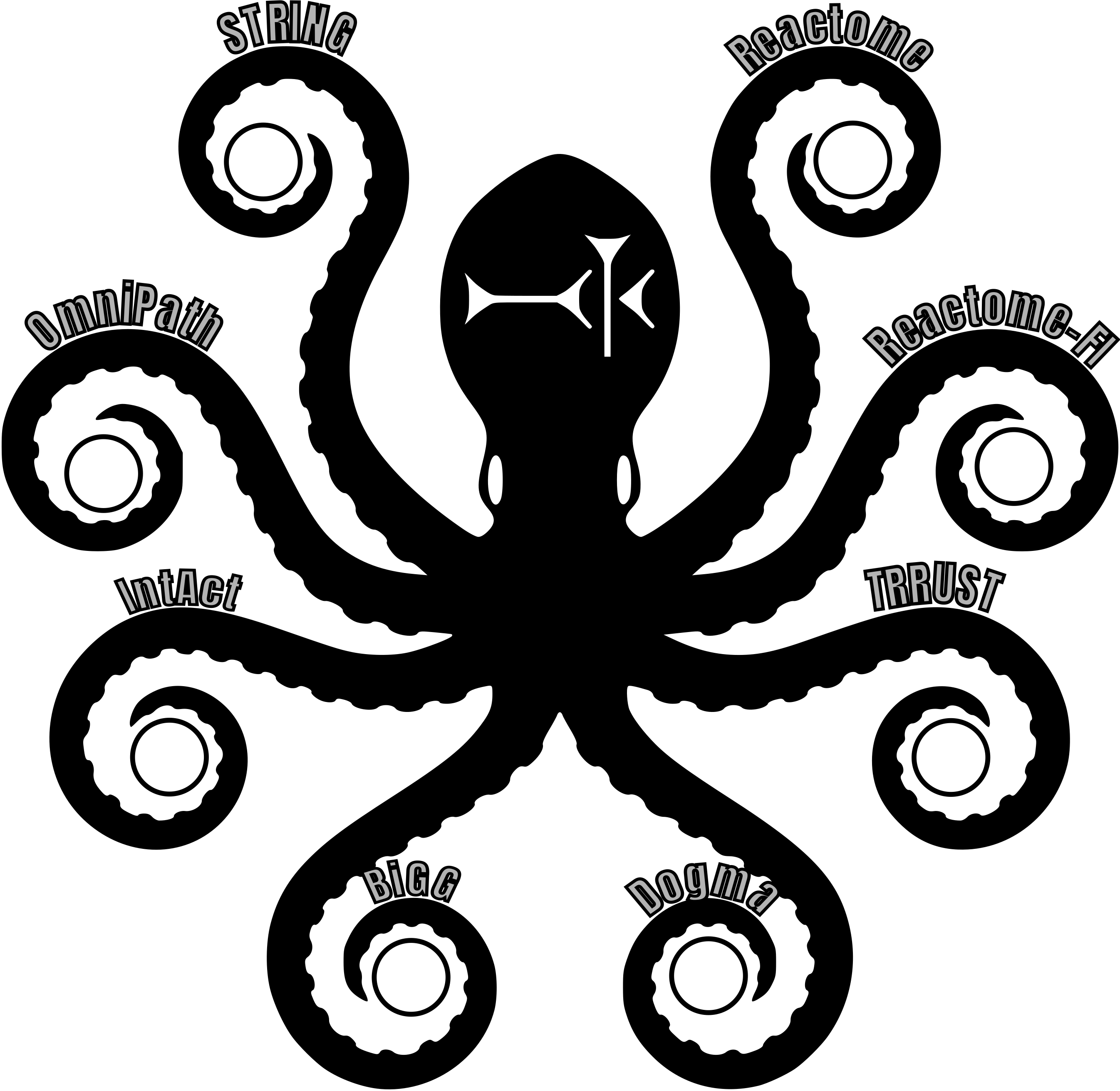

Anatomy of the Napistu MCP server

Before diving into the technical implementation, it’s worth understanding why I built this system. The Napistu MCP server serves three key purposes:

- Dramatically lowers the barrier to entry for new users who struggle with the “cold start” problem

- Democratizes domain expertise to encourage broader community contributions

- Gives core developers’ AI agents comprehensive project knowledge to efficiently extend the codebase

These objectives directly address the information fragmentation and context limitations we identified earlier. With this motivation in mind, I’ll provide an overview of the server’s architecture.

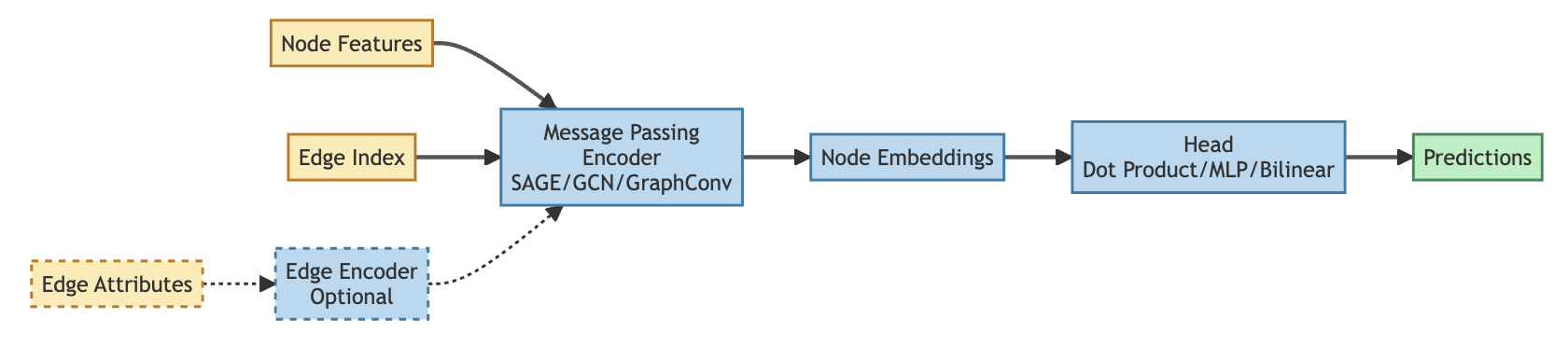

FastMCP foundation

The Model Context Protocol provides a standard way for AI models to access external information. FastMCP provides a Flask-like Python implementation of the MCP protocol.

from fastmcp import FastMCP

mcp = FastMCP("napistu-server")

@mcp.resource("napistu://health")

async def health_check():

return {"status": "healthy", "components": [...]}

@mcp.tool()

async def search_documentation(query: str) -> dict:

return {"results": [...]}

FastMCP manages the protocol details, while we focus on exposing Napistu’s knowledge.

The server.py module orchestrates the entire lifecycle through a

simple three-step process:

- Create a FastMCP server instance with the validated host, port, and server name from a standard, or manually defined, configuration.

- Based on the selected profile (execution, docs, or full), register the enabled components with the server; each component adds its own resources and tools to the endpoint registry.

- Asynchronously initialize all registered components, loading their data sources and setting up semantic search indexing in parallel.

Once this process completes, the server starts listening for incoming MCP requests.

Components

Napistu employs a component-based architecture that ensures separation of concerns — each component manages its own data sources and search logic. This design supports graceful degradation; for instance, a failed GitHub API call won’t disrupt tutorial searches. It also enables flexible deployment, allowing the activation of only the necessary components. This modularity lets me create servers tailored to specific use cases—for example, a local server capable of executing Napistu code or a remote server focused solely on documentation.

The current components are:

- Documentation: READMEs, wiki pages, GitHub issues and PRs\

- Codebase: API documentation and function signatures sourced from Read The Docs\

- Tutorials: Jupyter notebooks converted into searchable Markdown\

- Execution (in development): Interaction with a live Python environment

- Health: Server monitoring and diagnostics for system components

Each component follows a consistent pattern: load data, register endpoints, and handle search.

class DocumentationComponent(MCPComponent):

async def initialize(self, semantic_search: SemanticSearch = None) -> bool:

"""Load READMEs, wiki pages, GitHub issues"""

# Load external data and populate component state

return success

def register(self, mcp: FastMCP) -> None:

"""Register resources and tools with MCP server"""

@mcp.tool()

async def search_documentation(query: str):

return self.state.semantic_search.search(query, "documentation")

It’s important to write detailed AI-first docstrings for MCP resources and tools. This information is available to most agents before they interact with the server’s endpoints, so it’s helpful to clarify when and when NOT to use the method. While all-caps and bold sections may seem a bit obnoxious to human readers, they do effectively draw an agent’s attention.

For example, here is part of the docstring for the search_codebase

tool:

**USE THIS WHEN:**

- Looking for specific Napistu functions, classes, or modules

- Finding API documentation for Napistu features

**DO NOT USE FOR:**

- General programming concepts not specific to Napistu

- Documentation for other libraries or frameworks

Smart search: semantic + vector embeddings

We support two search methods: exact keyword search (e.g.,

“create_consensus”) and semantic search (e.g., “How do I merge pathway

data?”). Semantic search is powered by a SemanticSearch object used

across components.

The pipeline includes:

- Content Processing: Load content and chunk long documents at natural boundaries

- Embedding Generation: Convert chunks to 384-dimensional vectors using all-MiniLM-L6-v2 sentence transformer, selected for its ease of implementation and effectiveness with general text

- Vector Storage: Store embeddings in ChromaDB, along with metadata to support fast similarity search

- Query Processing: Embed user queries and find nearest neighbors using cosine similarity

class SemanticSearch:

def __init__(self, persist_directory: str = "./chroma_db"):

self.client = chromadb.PersistentClient(path=persist_directory)

self.embedding_function = SentenceTransformerEmbeddingFunction(

model_name="all-MiniLM-L6-v2"

)

def search(self, query: str, collection_name: str):

# Convert query to vector, find similar content by cosine similarity

return similarity_results_with_scores

An early version of the server used

keyword-based search to comb through all of the cached information. The

results quality was massively improved, however, switching to

vector-based search required me to implement several new features. To

approach this problem, I worked with Claude to research different

approaches balancing projected performance against ease of

implementation and maintainability. Since Claude was performing well, I

chose to stick with it for implementing the semantic search

functionality instead of switching to Cursor. This worked well because I

could provide the entire napistu.mcp subpackage as context, and the

codebase was already well-structured. The system introduced unnecessary

complexity in a few areas — such as managing separate component-level

ChromaDB databases rather than a unified centralized database — but

overall, the implementation proceeded efficiently, and I had the

functionality up and running within a few hours.

While I maintain strict oversight of agents contributing to the

scientific portions of the Napistu codebase, I allow greater autonomy

for agents working on the development of the napistu.mcp subpackage.

To do this, I focus more on code review to validate the AI’s assumptions

(e.g., “do we really need to assign global variables?”), and to

suggest refactoring (e.g., “would creating a ServerProfile class

simplify component configuration?”). After a session of implementing

features in Claude, I’ve leveraged it to update the Napistu MCP server

wiki

with some additional guidance (e.g., “shorten 4-fold, remove this

section”). Maintaining this high-level documentation, accessible via

MCP, effectively helps agents “save their place” for future

development sessions.

The agent experience

With the server architecture in place, let’s explore how this translates to the actual user experience for both humans and AI agents. The MCP protocol uses structured JSON messages over HTTP, with one key advantage: both humans and AI agents interact through the same unified interface.

Human developers engage directly using the Napistu client utilities or the MCP command line interface.

from napistu.mcp.client import search_component

from napistu.mcp.config import production_client_config

config = production_client_config()

results = await search_component("documentation", "how to install Napistu", config=config)

AI agents (such as Claude, Cursor, or any MCP-compatible tool) send equivalent requests via their respective MCP client implementations.

For example, when an agent asks “How do I create consensus networks in Napistu?””, it automatically:

AI agents (like Claude, Cursor, or any MCP-compatible tool) send the same underlying requests but through their MCP client implementations. When an agent asks “How do I create consensus networks in Napistu?”, it automatically:

- Calls the

search_tutorialstool with the query - Receives structured results with similarity scores and content snippets

- May follow up with

search_documentationorsearch_codebasefor additional context - Uses all this information to provide comprehensive, accurate guidance.

The key insight is that agents receive the same rich, structured responses as human developers but can instantly process and integrate information across multiple sources. This transforms a simple Q&A interaction into an expert-level consultation.

From local to global: deployment story

Local development

It’s easy to set up a local MCP server that digests relevant documents and interacts with local agents.

# Install Napistu with MCP dependencies

pip install 'napistu[mcp]'

# Start full development server (all components)

python -m napistu.mcp server full

# Health check shows component loading

python -m napistu.mcp health --local

🏥 Napistu MCP Server Health Check

Server URL: http://127.0.0.1:8765/mcp

Server Status: healthy

Components:

✅ documentation: healthy

✅ codebase: healthy

✅ tutorials: healthy

✅ semantic_search: healthy

This local approach works well for individual developers, but creates barriers for broader adoption. It requires installing Napistu, maintaining a background process, and keeping it running — imposing a significant burden on users who simply want to explore the project or collaborate.

The always-up solution

Instead, I aimed to create an always-available service that I and others access easily, without any local setup. This meant deploying the server to the cloud with automatic updates triggered by changes in codebase, integrated seamlessly into my GitHub Actions CI/CD workflows.

Every tagged release triggers deployment to Google Cloud Run.

# Deploy workflow - simplified view

on:

workflow_run:

workflows: ["Release"] # Auto-deploy after successful release

types: [completed]

schedule:

- cron: '0 10 * * *' # Daily content refresh at 2 AM PST (10 AM UTC)

jobs:

deploy:

steps:

- name: Deploy to Cloud Run

run: |

gcloud run deploy napistu-mcp-server \

--image="us-west1-docker.pkg.dev/.../napistu-mcp-server:latest" \

--cpu=1 --memory=2Gi \

--set-env-vars="MCP_PROFILE=docs"

The production setup runs the “docs” profile (documentation + codebase +

tutorials, no execution component since these are meant to operate in a

user environment) with 1 CPU and 2Gi memory, costing less than $1 per

day. Content is refreshed both upon new release of napistu-py and

nightly to ensure the latest documentation changes are captured.

This deployment strategy creates a powerful feedback loop between development and documentation.

The payoff

Now any AI tool can access the Napistu knowledge base instantly at https://napistu-mcp-server-844820030839.us-west1.run.app. Users don’t need to install software, run local processes, or handle maintenance; they can simply configure their AI tools to connect to the shared knowledge base. The service automatically updates with the latest documentation and code changes, while Google Cloud Run handles scaling, health checks, and automatic restarts to ensure high availability.

// Claude Desktop / Cursor configuration

// Add this to your MCP settings to access Napistu knowledge

{

"mcpServers": {

"napistu": {

"command": "npx",

"args": ["mcp-remote", "https://napistu-mcp-server-844820030839.us-west1.run.app/mcp/"]

}

}

}

The result is clear: Napistu’s entire knowledge base becomes instantly searchable by AI agents worldwide, dramatically lowering the barrier to contribution and collaboration.

🛡️ Security and privacy

The remote Napistu MCP server is intended for narrowly-scoped information retrieval, so security and privacy issues should be minimal:

- Scoped to Napistu-specific resources only

- No user data stored or processed. Standard cloud platform logging may occur because this runs on Google Cloud Run

- Auditable: all resources and tools are openly available in the public GitHub repository

Case studies: AI agents in action

As previously noted, the server’s core goals are to make the codebase more accessible to new users and collaborators, while also enhancing the capabilities of AI agents used by core developers. In this section, I’ll present two case studies that A/B test the impact of the MCP server on both onboarding and development experiences. In both cases, even when MCP was not enabled, I provided substantial contextual information through standard channels — Claude accessed files via GitHub, and Cursor had access to the full codebase. This makes MCP’s impact less binary and instead highlights its marginal contributions in more realistic, real-world scenarios.

Case Study 1: Learning with Claude

To illustrate MCP’s value for training, I provided Claude the same prompt both with and without MCP enabled for comparison:

I’m new to Napistu. Can you provide a high-level overview of the structure, creation, and usage of SBML_dfs? Please think deeply and incorporate your response into a Markdown file.

Without MCP

The resulting artifact is a mixed bag:

- ✅ Provides a good overview of the core and optional tables and their relationships.

- ✅ Public methods are grouped logically, with some light-weight explanations.

- ✅ Most code appears syntactically correct.

- ❌ Logistically, I had to manually add select files from GitHub which requires prior knowledge of the codebase — something a new user would likely lack.

- ❌ The “Creating SBML_dfs Objects” section mentions a subset of the approaches and includes the consensus logic, which feels out of place.

- ❌ Advanced usage and “integration with the Napistu ecosystem” consists of random functionality inferred from the CLI.

With MCP

Armed with the MCP, the artifact is well rounded, but far from perfect.

- ✅ Good overview of the core and optional tables and their relationships.

- ✅ Good high-level overview of how to create SBML_dfs and its public methods.

- ✅ Advanced usage, best practices, and general use cases are solid

- ❌

model_source = source.Source("MyDatabase", "v1.0"). This line captures the gist of themodel_sourceobject, but it won’t actually run. Since this was a new addition to the codebase, this is probably a case where the documentation has lagged behind the code. This serves as a helpful reminder that you’ll only get relevant information when your sources are up-to-date.

I definitely prefer the artifact generated with MCP, although it was generated from a single initial prompt. In the absence of MCP, follow-up questions by a user would quickly devolve into hallucinations. With access to the Napistu MCP, Claude can continue to guide the user through the complex codebase while maintaining a high-level perspective.

The Result: From “intimidating research codebase” to “approachable, guided experience”

Case Study 2: Building with Cursor

There are several areas where access to the MCP server would significantly benefit Cursor:

- 🚀 When NOT working on the actual Napistu codebase, Cursor could still look up classes and functions.

- 🚀 For general usage questions and training prompts, as demonstrated in Case Study 1, having access to related content and leveraging semantic search to handle synonyms would be especially valuable. However, this is not a major Cursor use case, and users would likely receive better responses from a general-purpose LLM like Claude in such scenarios.

And, situations where having access to the Napistu MCP would be entirely unnecessary:

- 🤷 When working directly on the Napistu codebase, Cursor can efficiently look up function signatures and search for functionality using its native methods.

Rather than setting up a strawman by denying Cursor access to the codebase, I wanted to explore scenarios when MCP could help Cursor in more nuanced situations. In exploring this question, I asked Cursor directly — and I found its response quite insightful.

MCP tools in Cursor are about bridging the gap between “what the code can do” and “how it’s meant to be used”. They’re not replacing code navigation; rather, they’re adding the intent and context that lives in documentation and tutorials.

Intent and context become particularly relevant when applying a framework like Napistu, rather than directly extending it. In this sense, the Napistu MCP is particularly valuable when using Napistu to explore scientific questions within a notebook environment. Given that Cursor recently added support for Jupyter notebooks (albeit still in an early and somewhat rough state), this represents a particularly compelling use case. To make the tasks straightforward, I asked Cursor to extend one of the Napistu tutorials because tutorials should be a mix of code and explanatory prose, just like a good biological analysis:

Can you help me extend the

understanding_sbml_dfs.ipynbtutorial to flesh out the “from_edgelist” workflow and to include any recent updates to the core data structure? THINK DEEPLY AND (DO NOT USE THE NAPISTU MCP / USE THE NAPISTU MCP AS NEEDED). Since you’ll have trouble directly editing the ipynb, please suggest what I should incorporate in a separate Markdown file. Edit for readability and to prioritize high value content. Limit the total content to less than 30 new sentences.

Without MCP

The artifact has its high and low points:

- ✅ The summary of the edgelist format with running code is quite good.

- ❌ It has no idea what I meant by “recent updates” and just provides code snippets for random public functions.

With MCP

Third-party integrations with Cursor are in a far rawer state than the

major models, so you really have to twist its arm to use it. In

practice, the experience is underwhelming — Cursor tends to rely

solely on the search_codebase tool, which surfaces information it

already has access to. As a result, the actual

output is

fairly poor:

- ❌ Only pseudocode describing the edgelist format

- ❌ Misinterprets “recent updates,” instead listing all public methods not already covered in the tutorial

Between these two scenarios, I would choose the output generated without MCP access. Much of this comes down to how Cursor used the MCP server. It tends to follow a one-track mindset — fixated on “code, code, code” — even when equipped with tools that could broaden its scope. The key takeaway is that the agentic coding space still has significant room to mature, particularly in fields like computational biology, where effective work demands both technical execution and deep domain insight.

Agents for science

In this post, I’ve shared how I’ve improved my AI-based code development experience by creating a remote Model Context Protocol (MCP) server for my scientific codebase, Napistu. The server delivers on-demand, contextually relevant information to AI agents, enabling them to efficiently surface relevant heterogeneous information and synthesize this information into actionable guidance. By deploying the server to Google Cloud Run via GitHub Actions, it can easily be used by both new and advanced users, at little cost to me.

To clarify the benefits of on-demand context, I provided case studies comparing agent behavior with and without access to the MCP server. These examples highlight the server’s impact on both onboarding efficiency and the overall development experience.

What’s next

More content

- External library documentation: Because the codebase is formatted by directly scraping the Read the docs, it would be straightforward to ingest documentation for non-Napistu libraries like igraph.

- More Napistu docs: Include the Napistu CLI, and READMEs, and the napistu.r’s pkgdown site.

- Supporting multiple Napistu versions: By preparing the core data as part of Napistu’s CI/CD workflow and saving the results to GCS, the server can download and cache a local version based on the user’s request.

More power

- Cross component semantic search: This would allow agents to search across multiple components, providing a more comprehensive understanding of the codebase.

- Execution components running Napistu functions: The execution components enable agents to register Python objects and apply transformations using Napistu functions. While still experimental, these components would allow agents to execute multiple steps in a live Python environment (like looking up two genes and finding the shortest path between them, entirely within the execution context).

More science

- Planning features and updating documentation with Claude

- Efficiently implementing features and squashing bugs in Cursor

🔧 Getting Started

Want to explore or contribute?

- Configure Claude Desktop or your favorite LLM with the MCP server.

- Ask questions about Napistu’s internals and architecture.

- Start contributing to open issues with AI-assisted development.

- Join our community discussions to collaborate, share ideas, and help shape the project.

Leave a comment